Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 2002

Les thèmes de la géopolitique et de l'espace russe dans la vie culturelle berlinoise de 1918 à 1945

Karl Haushofer, Oskar von Niedermayer & Otto Hoetzsch

Intervention de Robert Steuckers à la 10ième Université d'été de «Synergies Européennes», Basse-Saxe, août 2002

Analyse : Karl SCHLÖGEL, Berlin Ostbahnhof Europas - Russen und Deutsche in ihrem Jarhhundert, Siedler, Berlin, 368 S., DM 68, 1998, ISBN 3-88680-600-6.

En 1922, après l'effervescence spartakiste qui venait de secouer Berlin et Munich, un an avant l'occupation franco-belge de la Ruhr, le Général d'artillerie bavarois Karl Haushofer, devenu diplômé en géographie, est considéré, à l'unanimité et à juste titre, comme un spécialiste du Japon et de l'espace océanique du Pacifique. Son expérience d'attaché militaire dans l'Empire du Soleil Levant, avant 1914, et sa thèse universitaire, présentée après 1918, lui permettent de revendiquer cette qualité. Haushofer entre ainsi en contact avec deux personnalités soviétiques de premier plan: l'homme du Komintern à Berlin, Karl Radek, et le Commissaire aux affaires étrangères, Georgi Tchitchérine (qui signera les accords de Rapallo avec Rathenau). Dans quel contexte cette rencontre a-t-elle eu lieu? Le Japon et l'URSS cherchaient à aplanir leurs différends en entamant une série de négociations où les Allemands ont joué le rôle d'arbitres. Ces négociations portent essentiellement sur le contrôle de l'île de Sakhaline. Les Japonais réclament la présence de Haushofer, afin d'avoir, à leurs côtés "une personnalité objective et informée des faits". Les Soviétiques acceptent que cet arbitre soit Karl Haushofer, car ses écrits sur l'espace pacifique —négligés en Allemagne depuis que celle-ci a perdu la Micronésie à la suite du Traité de Versailles— sont lus avec une attention soutenue par la jeune école diplomatique soviétique. Qui plus est, avec la manie hagiographique des révolutionnaires bolcheviques, Haushofer a connu les frères Oulianov (Lénine) à Munich avant la première guerre mondiale; il aimait en parler et relatera plus tard ce fait dans ses souvenirs. L'intérêt soviétique pour la personne du Général Haushofer durera jusqu'en 1938, où, changement brusque d'attitude lors des grandes procès de Moscou, le Procureur réclame la condamnation de Sergueï Bessonov, qu'il accuse d'être un espion allemand, en contact, prétend-il, avec Haushofer, Hess et Niedermayer (cf. infra). Les mêmes accusations avaient été portées contre Radek, qui finira exécuté, lors des grandes purges staliniennes.

Ces trois faits d'histoire —la présence de Haushofer lors des négociations entre Japonais et Soviétiques, le contact, sans doute fort bref et parfaitement anodin, entre Haushofer et Lénine, les condamnations et exécutions de Radek et de Bessonov— indiquent qu'indépendamment des étiquettes idéologiques de "gauche" ou de "droite", la géopolitique, telle qu'elle est théorisée par Haushofer à Munich et à Berlin dans les années 20, ne s'occupe que du rapport existant entre la géographie et l'histoire; elle est donc considérée comme une démarche scientifique, comme un savoir pratique et non pas comme une spéculation idéologique ou occultiste, véhiculant des fantasmes ou des intérêts. A l'époque, on peut parler d'une véritable "Internationale de la géopolitique", transcendant largement les étiquettes idéologiques, tout comme aujourd'hui, un savoir d'ordre géopolitique, éparpillé dans une multitude d'instituts, commence à se profiler partout dans un monde où les grands enjeux géopolitiques sont revenus à l'ordre du jour : la question des Balkans, celle de l'Afghanistan, remettent à l'avant-plan de l'actualité toutes les grandes thématiques de la géopolitique, notamment celles qu'avaient soulignées Mackinder et Haushofer.

Une démarche factuelle et matérielle, sans dérive occultiste

A partir de 1924, Haushofer publie sa Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (ZfG; "Revue pour la géopolitique"), où il met surtout l'accent sur l'espace du Pacifique, comme l'attestent ses articles et sa chronique, rédigée notamment grâce à des rapports envoyés par des correspondants japonais. La teneur de cette revue est donc politique et géographique pour l'essentiel, contrairement aux bruits qui ont couru pendant des décennies après 1945, et qui commencent heureusement à s'atténuer; ces "bruits" évoquaient une fantasmagorique dimension "ésotérique" de la Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (ZfG); on a raconté que Haushofer appartenait à toutes sortes de sectes ésotériques ou occultes (voire occultistes). Ces allégations sont bien sûr complètement fausses. De plus, l'intérêt porté à Haushofer et à ses thèses sur l'espace du Pacifique par la jeune diplomatie soviétique, par Radek et Tchitchérine, est un indice complémentaire —et de taille!— pour attester de la nature factuelle et matérielle de ses écrits; les sectes étant par définition irrationnelles, comment un homme, que l'on dit plongé dans cet univers en marge de toute rationalité scientifique, aurait pu susciter l'intérêt et la collaboration active de marxistes matérialistes et historicistes? De marxistes qui tentent d'expurger toute irrationalité de leurs démarches intellectuelles? L'accusation d'occultisme portée à l'encontre de Haushofer est donc une contre-vérité propagandiste, répandue par les services et les puissances qui ont intérêt à ce que son œuvre demeure inconnue, ne soit plus consultée dans les chancelleries et les états-majors. Il va de soi qu'il s'agit des puissances qui ont intérêt à ce que le grand continent eurasien ne soit pas organisé ni aménagé territorialement jusqu'en ses régions les plus éloignées de la mer.

Le principal ouvrage géopolitique et scientifique de Haushofer est donc sa Geopolitik des Pazifischen Raumes ("Géopolitique de l'espace pacifique"), livre de référence méticuleux qui se trouvait en permanence sur le bureau de Radek, à Berlin comme à Moscou. Karl Radek jouait le rôle du diplomate du PCUS ("Parti communiste d'Union Soviétique"). Il a cependant plaidé, au moment où les Français condamnent à mort et font fusiller l'activiste nationaliste allemand Albert Leo Schlageter, pour un front commun entre nationaux et communistes contre la puissance occidentale occupante. Plus tard, Radek sera nommé Recteur de l'Université Sun-Yat-Sen à Moscou, centre névralgique de la nouvelle culture politique internationale que les Soviets entendent généraliser sur toute la planète. Radek organisera, au départ de cette université d'un genre nouveau, un échange permanent entre universitaires, dont le savoir est en mesure de forger cette nouvelle culture diplomatique internationale.

Trois figures emblématiques

Dans le cadre de cette Université Sun-Yat-Sen , trois figures emblématiques méritent de capter aujourd'hui encore notre attention, tant leurs démarches peuvent encore avoir une réelle incidence sur toute réflexion actuelle quant au destin de la Russie, de l'Europe, de l'Asie centrale et quant aux théories générales de la géopolitique: Mylius Dostoïevski, Richard Sorge et Alexander Radós.

Mylius Dostoïevski est le petit-fils du grand écrivain russe. Qui, rappelons-le, a jeté les bases d'une révolution conservatrice en Russie, au-delà des limites de la slavophilie du début du 19ième siècle, et a consolidé, par ricochet, la dimension russophile de la révolution conservatrice allemande, par le biais de ses réflexions consignées dans son Journal d'un écrivain, ouvrage capital qui sera traduit en allemand par Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. Mylius Dostoïevski s'était spécialisé en histoire et en géographie du Japon, de la Chine et de l'espace maritime du Pacifique. Il appartiendra à la jeune garde de la diplomatie soviétique et sera un lecteur attentif de la ZfG; pour rendre la politesse à ces jeunes géographes soviétiques, selon sa courtoisie habituelle, Karl Haushofer rendra toujours compte, avec précision, des évolutions diverses de la nouvelle géopolitique soviétique. Il estimait que les Allemands de son temps devaient en connaître les grandes lignes et la dynamique.

Richard Sorge, autre lecteur de la ZfG, était un espion soviétique en Extrême-Orient. On connaît son rôle pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. En 1933, au moment où Hitler prend le pouvoir en Allemagne, Sorge était en contact avec l'école géopolitique de Haushofer. Il le restera, en dépit du changement de régime et en dépit des options anti-communistes officielles, preuve supplémentaire que la géopolitique se situe bien au-delà des clivages idéologiques et politiciens. Au cours des années qui suivirent la "Machtübernahme" de Hitler, il écrivit de nombreux articles substantiels dans la ZfG. Sa connaissance du monde extrême-oriental —et elle seule— justifiait cette collaboration.

Alexander Radós et "Pressgeo"

Indubitablement, le principal disciple soviétique de Karl Haushofer a été l'Israélite hongrois Alexander Radós, un géographe de formation, qui a servi d'espion au profit de la jeune URSS, notamment en Suisse, plaque tournante de nombreux contacts officieux. Radós est l'homme qui a forgé tous les nouveaux concepts de la géographie politique soviétique. Il est, entre autres, celui qui forgea la dénomination même d'«Union des Républiques Socialistes Soviétiques». Radós fut principalement un cartographe, qui a commencé sa carrière en établissant des cartes du trafic aérien, lesquelles constituaient évidemment une innovation à son époque. Il enseignait à l'«Ecole marxiste de formation des Travailleurs» ("Marxistische Arbeiterschulung"). Il fonde ensuite la toute première agence de presse cartographique du monde, qu'il baptise "Pressgeo", où travaillera notamment une future célébrité comme Arthur Koestler. La fondation de cette agence correspond parfaitement aux aspirations de Haushofer, qui voulait vulgariser —et diffuser au maximum au sein de la population— un savoir pragmatique d'ordre géographique, historique et économique, assorti d'un esprit de défense. La carte, esquisse succincte, instrument didactique de premier ordre, sert l'objectif d'instruire rapidement les esprits décisionnaires des armées et de la diplomatie, ainsi que les enseignants en histoire et en science politique qui doivent communiquer vite un savoir essentiel et vital à leurs ouailles.

Haushofer parlait aussi, en ce sens, de "Wehrgeographie", de "géographie défensive", soit de "géographie militaire". L'objectif de cette science pragmatique était de synthétiser en un simple coup d'œil cartographique toute une problématique de nature stratégique, récurrente dans l'histoire. Pédagogie et cartographie formant les deux piliers majeurs de la formation politique des élites et des masses. Yves Lacoste, en France aujourd'hui, suit une même logique, en se référant à Elisée Reclus, géographe dynamique, réclamant une pédagogie de l'espace, dans une perspective qu'il voulait révolutionnaire et "anarchique". Lacoste, comme Haushofer, a parfaitement conscience de la dimension militaire de la géographie (et, a fortiori, de la "Wehrgeographie"), quand il écrit, en faisant référence aux premiers cartographes militaires de la Chine antique: «La géographie, ça sert à faire la guerre!».

De l'utilité pédagogique de la cartographie

Michel Foucher, professeur à Lyon, dirige aujourd'hui un institut géographique et cartographique, dont les cartes, très didactiques, illustrent la majeure partie des organes de presse français, quand ceux-ci évoquent les points chauds de la planète. Dans ce même esprit pluridisciplinaire, à volonté clairement pédagogique, —qui, en France et en Allemagne, va de Haushofer à Lacoste et à Foucher— Alexander Radós, leur précurseur soviétique, publie, en URSS et en Allemagne, en 1930, un Atlas für Politik, Wirtschaft und Arbeiterbewegung ("Atlas de la politique, de l'économie et du mouvement ouvrier"). Radós est ainsi le précurseur d'une manière innovante et intéressante de pratiquer la géographie politique, de mêler, en d'audacieuses synthèses, un éventail de savoirs économiques, géographiques, militaires, topographiques, géologiques, hydrographiques, historiques. Les synthèses, que sont les cartes, doivent servir à saisir d'un seul coup d'œil des problématiques hautement complexes, que le simple texte écrit, trop long à assimiler, ne permet pas de saisir aussi vite, d'exprimer sans détours inutiles. Ce fut là un grand pas en avant dans la pédagogie scientifique et politique, dans le sens inauguré, un siècle auparavant, par le géographe Carl Ritter.

Cette cartographie facilite le travail du militaire, du géographe et de l'homme politique; elle permet, comme le soulignait Karl August Wittfogel, de sortir d'une impasse de la vieille science géographique traditionnelle (et "réactionnaire" pour les marxistes), où, systématiquement, on avait négligé les macro-processus enclenchés par le travail de l'homme et, ainsi, le caractère "historique-plastique" de ce que l'on croyait être des "faits éternels de nature". C'est dans cette position épistémologique fondamentale, qu'au-delà des clivages idéologiques, fruits d'"éthiques de la conviction" aux répercussions calamiteuses, se rejoignent Elisée Reclus, Haushofer, Radós, Wittfogel, Lacoste et Foucher. Wittfogel , qui se pose comme révolutionnaire, reconnaît cette "plasticité historique" dans l'œuvre du "géopolitologue bourgeois" Karl Haushofer. Les deux écoles, l'haushoférienne et la marxiste, veulent inaugurer une géographie dynamique, où l'espace n'est plus posé comme un bloc inerte et immobile, mais s'appréhende comme un réseau dense de relations, de rapports, de mouvements, en perpétuelle effervescence (on songe tout naturellement au "rhizome" de Gilles Deleuze, qui inspire les "géophilosophes" italiens actuels). Au sein de ce réseau toujours agité, le temps peut apporter des époques de repos, de plus grande quiétude, comme il peut injecter du dynamisme, de la violence, des bouleversements, qui contraignent les personnalités politiques de valeur à œuvrer à des redistributions de cartes. Le travail de l'homme, qui domestique certains espaces en les aménageant et en créant des moyens de communication plus rapides, est un travail proprement "révolutionnaire"; les hommes politiques qui refusent d'aménager l'espace, dans un esprit de défense territoriale ou dans l'esprit d'assurer aux générations futures communications et ressources, sont des "réactionnaires", des lâches qui préfèrent de lents pourrissements à la dynamique de transformation. Des capitulards qui font ainsi le jeu pervers des thalassocraties.

Par conséquent, évoquer des hommes comme Mylius Dostoïevski, Richard Sorge, Alexander Radós ou Karl August Wittfogel, nous apparaît très utile, intellectuellement et méthodologiquement, car cela prouve:

◊ que l'intérêt général pour la géopolitique aujourd'hui ne peut plus être mis en équation avec un intérêt malsain pour le passé national-socialiste (contexte dans lequel Haushofer a dû œuvrer);

◊ qu'aucune morbidité d'ordre ésotérique ou occultiste ne se repère dans l'œuvre de Haushofer et de ses disciples allemands ou soviétiques;

◊ que ces écoles ont posé d'important jalons dans le développement de la science politique, de la géographie et de la cartographie;

◊ qu'elles ont laissé en héritage un bagage scientifique de la plus haute importance;

◊ que nous devrions davantage nous intéresser aux développements de la géopolitique soviétique des années 20 et 30 (et analyser l'œuvre de Radós, par exemple).

Oskar von Niedermayer, le "Lawrence allemand"

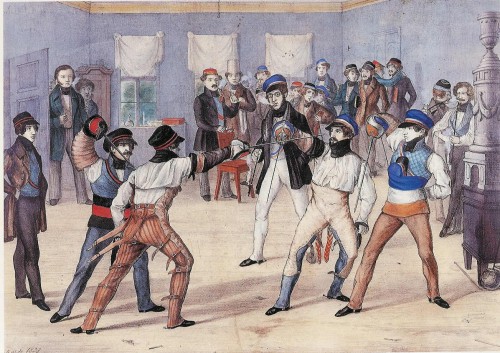

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement leurs fronts en Europe, dans le Caucase et en Mésopotamie. Cette mission sera un échec. En 1919, Niedermayer se retrouve dans les rangs du Corps Franc du Colonel Chevalier Franz von Epp qui écrase la République des Conseils de Munich. En dépit de son rôle dans l'aventure de ce Corps Franc anti-communiste, Niedermayer est nommé dans la foulée officier de liaison de la Reichswehr auprès de la nouvelle Armée Rouge à Moscou. Dans ce contexte, il est intéressant de noter qu'il était, avant toutes choses, un expert de l'Afghanistan, des idiomes persans et de toute cette zone-clef de la géostratégie mondiale qui va de la rive sud de la Caspienne à l'Indus. C'est donc Niedermayer qui négociera avec Trotski et qui visitera, pour le compte de la Reichswehr, dans la perspective de la future coopération militaire entre les deux pays, les usines d'armement et les chantiers navals de Petrograd (devenue "Leningrad"). Oskar von Niedermayer a donc été l'une des chevilles ouvrières de la coopération militaire et militaro-industrielle germano-russe des années 20. En 1930, il devient professeur de "Wehrgeographie" à Berlin.

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement leurs fronts en Europe, dans le Caucase et en Mésopotamie. Cette mission sera un échec. En 1919, Niedermayer se retrouve dans les rangs du Corps Franc du Colonel Chevalier Franz von Epp qui écrase la République des Conseils de Munich. En dépit de son rôle dans l'aventure de ce Corps Franc anti-communiste, Niedermayer est nommé dans la foulée officier de liaison de la Reichswehr auprès de la nouvelle Armée Rouge à Moscou. Dans ce contexte, il est intéressant de noter qu'il était, avant toutes choses, un expert de l'Afghanistan, des idiomes persans et de toute cette zone-clef de la géostratégie mondiale qui va de la rive sud de la Caspienne à l'Indus. C'est donc Niedermayer qui négociera avec Trotski et qui visitera, pour le compte de la Reichswehr, dans la perspective de la future coopération militaire entre les deux pays, les usines d'armement et les chantiers navals de Petrograd (devenue "Leningrad"). Oskar von Niedermayer a donc été l'une des chevilles ouvrières de la coopération militaire et militaro-industrielle germano-russe des années 20. En 1930, il devient professeur de "Wehrgeographie" à Berlin.

Le "marais" et ses éthiques de conviction

La principale leçon qu'il tire de ses activités politiques et diplomatiques est une méfiance à l'endroit des politiciens du "centre", du "marais", incapables de comprendre les grands ressorts de la politique internationale, du "Grand Jeu". Ses critiques s'adressaient surtout aux sociaux-démocrates et aux centristes de tous plumages idéologiques; avec de tels personnages, il est impossible, constate von Niedermayer dans un rapport où il ne cache pas son amertume, d'articuler sur le long terme une politique étrangère durable, rationnelle et constante. Il les accuse de tout critiquer publiquement, par voie de presse; de cette façon, aucune diplomatie secrète n'est encore possible. Pire, estime-t-il, par le comportement délétère de ces bateleurs sans épine dorsale politique solide, aucun ressort habituel de la diplomatie inter-étatique ne fonctionne encore de manière optimale. Car les éthiques de conviction (terminologie de Max Weber: "Gesinnungsethik") qui animent toutes les vaines agitations politiciennes de ces gens-là, altèrent l'esprit de retenue, de sérieux et de service, qui est nécessaire pour faire fonctionner une telle diplomatie traditionnelle. La priorité accordée aux convictions revient à trahir les intérêts fondamentaux de l'Etat et de la nation. L'amertume de Niedermayer est née à la suite d'un incident au Reichstag, où le socialiste Scheidemann, animé par un pacifisme irréaliste et de mauvais aloi, avait dénoncé un accord militaire secret entre l'URSS et le Reich, sous prétexte que le commerce et l'échange d'armements ne sont pas "moraux". Le lendemain, comme par hasard, la presse londonienne à l'unisson, reprend l'information et amorce une propagande contre les deux puissances continentales, qui avaient contourné les clauses de Versailles relatives aux embargos. Cet incident montre aussi que bon nombre de journalistes servent des intérêts étrangers à leur pays. En cela, rien n'a changé aujourd'hui: les Etats-Unis bénéficient de l'appui inconditionnel de la plupart des ténors de la presse parisienne.

Youri Semionov, spécialiste de la Sibérie

Dans les années 30, Niedermayer rencontre Youri Semionov, Russe blanc en exil et spécialiste de l'économie, de la géographie, de la géologie et de l'hydrographie sibériennes. Semionov est l'auteur d'un ouvrage, toujours d'actualité, toujours compulsé en haut lieu, sur les trésors de la géologie sibérienne. Egalement spécialiste de l'empire colonial français, Semionov a compilé ses réflexions successives dans un volume dont la dernière édition allemande date de 1975 (cf. Juri Semjonow, Erdöl aus dem Osten - Die Geschichte der Erdöl- und Erdgasindustrie in der UdSSR, Econ Verlag, Wien/Düsseldorf, 1973 & Sibirien - Schatzkammer des Ostens, Econ Verlag, Wien/Düsseldorf, 1975). Né en 1894 à Vladikavkaz dans le Caucase, Youri Semionov a étudié à l'Université de Moscou, avant d'émigrer en 1922 à Berlin, où il enseignera l'histoire et la géographie de la Russie, et plus particulièrement celles des territoires sibériens. Après la chute du IIIe Reich, il émigre en 1947 en Suède, où il enseignera à Uppsala et finira ses jours. Dans Sibirien - Schatzkammer des Ostens, il retrace toutes les étapes de l'histoire de la conquête russe des territoires situés au-delà de l'ex-capitale des Tatars, Kazan. Il démontre que la conquête de tout le cours de la Volga, de Kazan à Astrakhan, permet à la Russie de spéculer sur une éventuelle conquête des Indes. Semionov replace tous ces faits d'histoire dans une perspective géopolitique, celle de l'organisation du Grand Continent, de la Mer Blanche au Pacifique. Les chapitres sur le 19ième siècle sont particulièrement intéressants, notamment quand il décrit la situation globale après la décision du Tsar Alexandre III de faire financer la construction d'un chemin de fer transsibérien.

Cet extrait du livre de Semionov (pp. 356-357) résume parfaitement cette situation : «Nous savons que toute la politique de "concentration des forces sur le continent", telle celle que l'on avait envisagée en Russie, provoquait une inquiétude faite de jalousie en Angleterre. Tout mouvement de la Russie en Asie y était considéré comme une menace pesant sur l'Inde. L'Amiral Sterling a vu cette menace se concrétiser dès l'installation de la présence russe le long du fleuve Amour. L'écrivain anglais, oublié aujourd'hui, mais très connu à l'époque, Th. T. Meadows, évoquait en 1856, dans un de ses écrits, un "futur Alexandre le Grand" russe, qui s'en irait conquérir la Chine, puis, sans difficulté aucune, détruirait l'empire britannique et soumettrait le monde entier. Ce cri d'alarme pathétique, répercuté par la presse anglaise, est apparu soudain très réaliste, lorsque, dans les années 80 du 19ième siècle, les Russes avancent en Asie centrale et s'approchent de la frontière afghane. En 1884, se déroule le fameux "incident afghan"; un détachement russe s'empare d'un point contesté sur la frontière; ensuite, les Afghans, qui agissaient sur ordre des Anglais, attaquent ce poste, mais sont battus et dispersés par les Russes. Le premier ministre britannique Gladstone déclare, face au Parlement de Londres, que la guerre avec la Russie est désormais inévitable. Seul le refus de Bismarck, de soutenir les Anglais, empêcha, à l'époque, le déclenchement d'une guerre anglo-russe». Toute l'actualité récente semble résumée dans ce bref extrait.

Les chapitres consacrés à l'œuvre de Witte, père du Transsibérien, sont également lumineux. Semionov rappelle que Witte est un disciple de l'économiste Friedrich List, théoricien de l'aménagement des grands espaces. Il existait, avant la première guerre mondiale et avant la guerre russo-japonaise, une véritable idée grande continentale. Elle était partagée en France (Henri de Grossouvre nous a rappelé l'œuvre de Gabriel Hanotaux), en Allemagne (avec le souvenir de Bismarck) et en Chine, avec Li Hung-Tchang, qui négociera avec Witte. L'Angleterre réussira à briser cette unité, ce qui entraînera le cortège sanglant de toutes les guerres du 20ième siècle.

Oskar von Niedermayer rencontre également le Professeur Otto Hoetzsch, dont nous allons retracer l'itinéraire dans la suite de cette intervention. En dépit de leurs itinéraires bien différents et de leurs options idéologiques divergentes, Haushofer, Niedermayer, Semionov et Hoetzsch se complètent utilement et la lecture simultanée de leurs œuvres nous permet de saisir toute la problématique eurasienne, sans la mutiler, sans rien omettre de sa complexité.

Du professorat à la 162ième Division

En 1937, Hitler ordonne la fondation d'un "Institut für allgemeine Wehrlehre" (= "Institut pour les doctrines générales de défense"). Niedermayer, bien que sceptique, servira loyalement cette nouvelle institution d'Etat, dont l'objectif, recentré sur l'ethnologie vu l'intérêt des nationaux-socialistes pour les questions raciales, est d'étudier les rapports mutuels entre peuple(s) et espace(s). Hostile à la "Gesinnungsethik" des nationaux socialistes, comme il avait été hostile à celles des sociaux démocrates ou des centristes, Niedermayer proteste contre les campagnes de diffamation orchestrées contre des professeurs que l'on décrit comme des "intellectuels apolitiques", comportement hitlérien qui trouve parfaitement son pendant dans les campagnes de diffamation orchestrées par un certain journalisme contemporain contre ceux qui demeurent sceptiques face aux projets d'éradiquer l'Irak, la Libye ou la Serbie et d'appuyer des bandes mafieuses comme celles de l'UÇK ou du complexe militaro-mafieux turc. Aujourd'hui, on ne traite pas ceux qui entendent raison garder d'"intellectuels apolitiques", mais d'"anti-démocrates".

De la prison de Torgau à la Loubianka

Comme la plupart des experts ès-questions russes de son temps, Niedermayer déplore la guerre germano-soviétique, déclenchée en juin 1941. En 1942, sur la suggestion de Claus von Stauffenberg, futur auteur de l'attentat du 20 juillet 1944 contre Hitler, Niedermayer est nommé chef de la 162ième Division d'Infanterie de la Wehrmacht, où servent des volontaires et des légionnaires de souche turque (issus des peuples turcophones d'Asie centrale). Cette unité connaît des fortunes diverses, mais l'échec de la politique nationale-socialiste à l'Est, accentue considérablement le scepticisme de Niedermayer. Stationné en Italie avec les restes de sa division, il critique ouvertement la politique menée par Hitler sur le territoire de l'Union Soviétique. Ce qui conduit à son arrestation; il est interné à Torgau sur l'Elbe. Quand les troupes américaines entrent dans la ville, il quitte la prison et est arrêté par des soldats soviétiques qui le font conduire immédiatement à Moscou, où il séjourne dans la fameuse prison de la Loubianka. Il y mourra de tuberculose en 1948.

La mort de Niedermayer ne clôt pas son "dossier", dans l'ex-URSS. En 1964, les autorités soviétiques utilisent les textes de ses dépositions à Moscou en 1945 pour réhabiliter le Maréchal Toukhatchevski. Il faudra attendra 1997 pour que Niedermayer soit lui-même totalement réhabilité. Donc lavé de toutes les accusations incongrues dont on l'avait chargé.

Le pivot indien de l'histoire et la nécessité du "Kontinentalblock"

Nous avons énuméré bon nombre de faits biographiques de Niedermayer, pour faire mieux comprendre le noyau essentiel de sa démarche d'iranologue, d'explorateur du Dacht-i-Lout, d'agitateur allemand en Afghanistan et de commandeur de la Division turcophone de la Wehrmacht. Deux idées de base animaient l'action de Niedermayer: 1) l'idée que l'Inde était le pivot de l'histoire mondiale; 2) la conscience de la nécessité impérieuse de construire un bloc continental (eurasien), le fameux "Kontinentalblock" de Karl Haushofer (projet qu'il a très probablement repris des hommes d'Etats japonais du début du 20ième siècle, tels le Prince Ito, le Comte Goto et le Premier Ministre Katsura, avocats d'une alliance grande continentale germano-russo-japonaise). Si Niedermayer reprend sans doute cette idée de "bloc continental" directement de l'œuvre de Haushofer, sans remonter aux sources japonaises —qu'il devait sûrement ignorer— l'idée de l'Inde comme "pivot de l'histoire" lui vient très probablement du Général Andreï Snessarev, officier tsariste passé aux ordres de Trotski, pour devenir le chef d'état-major de l'Armée Rouge. Ce général, hostile aux thalassocraties anglo-saxonnes, représentant d'un idéal géopolitique grand continental transcendant le clivage blancs/rouges, se plaisait à répéter: «Si nous voulons abattre la tyrannie capitaliste qui pèse sur le monde, alors nous devons chasser les Anglais d'Inde».

Principes thalassocratiques, libéralisme à l'occidentale, permissivité politique et morale, capitalisme dont les ressorts annihilent systématiquement les traditions historiques et culturelles (cf. Dostoïevski et Moeller van den Bruck), logique marchande, étaient synonymes d'abjection pour cet officier traditionnel: peu importe qu'on les combatte sous une étiquette blanche/traditionaliste ou sous une étiquette rouge/révolutionnaire. Les étiquettes sont des "convictions" sans substance: seule importe une action constante visant à réduire et à détruire les forces dissolvantes de la modernité marchande, car elles conduisent le monde au chaos et les peuples à une misère sans issue. Comme nous le constatons encore plus aujourd'hui qu'à l'époque, l'industriel, le négociant et le banquier, avec leur logique d'accumulation monstrueuse, apparaissent comme des êtres aussi abjects qu'inférieurs, foncièrement malfaisants, pour cet officier supérieur russe et soviétique qui ne respecte que les hommes de qualité: les historiens, les prêtres, les soldats et les révolutionnaires. Les impératifs de la géopolitique sont des constantes de l'histoire auquel l'homme de longue mémoire, seul homme valable, seul homme pourvu de qualités indépassables, se doit d'obéir. A la suite de ce Snessarev, qu'il a sans doute rencontré au temps où il servait d'officier de liaison auprès de l'Armée Rouge, Niedermayer, fort également de ses expériences d'iranologue, d'explorateur du Dacht-i-Lout et de spécialiste de l'Afghanistan, clef d'accès aux Indes depuis Alexandre le Grand, savait que le destin de l'Europe en général, de l'Allemagne, son cœur géographique, en particulier, se jouait en Inde (et, partant, en Perse et en Afghanistan). Une leçon que l'actualité a rendue plus vraie que jamais.

Exporter la révolution et absorber le "rimland"

Pour Niedermayer, officier allemand, ce rôle essentiel du territoire indien pose problème car son pays ne possède aucun point d'appui dans la région, ni dans son environnement immédiat. La Russie tsariste, oui, et, à sa suite, l'URSS, aussi. Par conséquent, les positions militaires soviétiques au Tadjikistan et le long de la frontière afghane, sont des atouts absolument nécessaires à l'Europe dans son ensemble, à toute la communauté des peuples de souche européenne. C'est la possession de cet atout stratégique en Asie centrale qui doit justifier, aux yeux de Niedermayer, l'indéfectible alliance germano-russe, seule garante de la survie de la culture européenne dans son ensemble. Pour les tenants du bolchevisme révolutionnaire autour de Trotski et Lénine, la solution, pour faire tomber le capitalisme, c'est-à-dire la puissance planétaire des thalassocraties libérales, réside dans la politique d'"exporter la révolution", d'agiter les populations colonisées et assujetties par un bon dosage de nationalisme et de révolution sociale. Ainsi, les puissances continentales de la "Terre du Milieu" pourront porter leurs énergies en direction du "rimland" indien, persan et arabe, réalisant du même coup les craintes formulées par Mackinder dans son discours de 1904 sur le "pivot" sibérien et centre-asiatique de l'histoire. Propos qu'il réitèrera dans son livre Democratic Ideals and Reality de 1919. Cependant, pour pouvoir libérer l'Inde et y exporter la révolution, il faut déjà un bloc continental bien soudé par l'alliance germano-soviétique, prélude à la libération de toute la masse continentale eurasiatique.

Pour structurer l'Europe: un chemin de fer à voies larges

Pour parfaire l'organisation de cette gigantesque masse continentale, il faut se rappeler et appliquer les recettes préconisées par le Ministre du Tsar, Sergueï Witte, père du Transsibérien. Dans le Berlin des années 20, un projet circule déjà et prendra corps pendant la seconde guerre mondiale: celui de réaliser un chemin de fer à voie large ("Breitspurbahn"), permettant de transporter un maximum de personnes et de marchandises, en un minimum de temps. Cette idée, venue de Witte, n'est pas entièrement morte, constitue toujours un impératif majeur pour qui veut véritablement travailler à la construction européenne: le Plan Delors, esquissé dans les coulisses de l'UE, préconisait naguère des grands travaux publics d'aménagement territorial, y compris un système ferroviaire rapide, désormais inspiré par le TGV français. En 1942, Hitler, en évoquant le Transsibérien de Witte, donne l'ordre à Fritz Todt d'étudier les possibilités de construire une "Breitspurbahn", avec des trains roulant entre 150 et 180 km/h pour le transport des marchandises et entre 200 et 250 km/h pour le transport des personnes. Le projet, confié à Todt, ne concerne pas seulement l'Europe, au sens restreint du terme, n'entend pas seulement relier entre elles les grandes métropoles européennes, mais aussi, via l'Ukraine et le Caucase, les villes d'Europe à celles de la Perse. Ces projets, qui apparaissaient à l'époque comme un peu fantasmagoriques, n'étaient nullement une manie du seul Hitler (et de son ingénieur Todt); en Union Soviétique aussi, via des romans populaires, comme ceux d'Ilf et de Petrov, on envisage la création de chemins de fer ultra-rapides, reliant la Russie à l'Extrême-Orient.

Le destin tragique du Professeur Otto Hoetzsch

Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement le résultat navrant de la destruction de la bibliothèque du Prof. Hoetzsch. En 1945 et en 1946, celui-ci, âgé de 70 ans, erre seul dans Berlin, privé de sa documentation; cet homme, brisé, trouve néanmoins le courage ultime de rédiger une conférence, la dernière qu'il donnera, où il nous lègue un véritable testament politique (titre de cette conférence : "Die Eingliederung des osteuropäischen Geschichte in die Gesamtgeschichte"; = L'inclusion de l'histoire est-européenne dans l'histoire générale).

Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement le résultat navrant de la destruction de la bibliothèque du Prof. Hoetzsch. En 1945 et en 1946, celui-ci, âgé de 70 ans, erre seul dans Berlin, privé de sa documentation; cet homme, brisé, trouve néanmoins le courage ultime de rédiger une conférence, la dernière qu'il donnera, où il nous lègue un véritable testament politique (titre de cette conférence : "Die Eingliederung des osteuropäischen Geschichte in die Gesamtgeschichte"; = L'inclusion de l'histoire est-européenne dans l'histoire générale).

Slaviste et historien de la Russie, Otto Hoetzsch s'était aperçu très tôt que les Européens de l'Ouest, les Occidentaux en général, ne comprenaient rien de la dynamique de l'histoire et de l'espace russes; ce que les Russes repèrent tout de suite, ce qui les navrent et les fâchent. Cette ignorance, assortie d'une prétention mal placée et d'une irrépressible et agaçante propension à donner des leçons, vaut également pour l'espace balkanique (sauf en Autriche où les instituts spécialisés dans le Sud-Est européen ont réalisé des travaux remarquables, dont les chancelleries occidentales ne tiennent jamais compte). Hoetzsch constate, dès le début de sa brillante carrière, que la presse ne produit que des articles lamentables, quand il s'agit de commenter ou de décrire les situations existantes en Russie ou en Sibérie. Il va vouloir remédier à cette lacune. A partir de 1913, il se met à rassembler une documentation, à étudier et à lire les grands classiques de la pensée politique russe, à lire les historiens russes, ce qui le conduira à fonder en 1925, quelques mois après la sortie du premier numéro de la ZfG de Haushofer, une revue spécialisée dans les questions russes et centre-asiatiques, Osteuropa. Captivé par la figure du Tsar Alexandre II, sur lequel il rédigera un maître-ouvrage, dont le manuscrit sera sauvé in extremis de la destruction à Berlin en 1945; Hoetzsch le transportait dans sa valise en fuyant Berlin en flammes. Pourquoi Alexandre II? Ce Tsar est un réformateur social, il lance la Russie sur la voie de l'industrialisation et de la modernisation, ce que ne peuvent tolérer les thalassocraties. Il périra d'ailleurs assassiné. En dépit du ressac de la Russie sous Nicolas II, de sa lourde défaite subie en 1905 face au Japon, armé par l'Angleterre et les Etats-Unis, en dépit du terrible ressac que constitue la prise du pouvoir par les Bolcheviques, l'œuvre d'Alexandre II doit, aux yeux de Hoetzsch, demeurer le modèle pour tout homme d'Etat russe digne de ce nom.

Ami des Russes blancs et "Républicain de Raison"

Hoetzsch est un libéral de gauche, proche de la sociale démocratie, mais il déteste les Bolcheviques, car, pour lui, ce sont des agents du capitalisme anglais, dans la mesure où ils détruisent l'œuvre des Tsars émancipateurs et modernistes; ils ont comploté contre ceux-ci et contre d'excellents hommes d'Etat comme Witte et Stolypine (qui sera également assassiné). Hoetzsch fréquente l'émigration blanche de Berlin, consolide son institut grâce aux collaborations des savants chassés par les Bolcheviques, mais reste ce que l'on appelait à l'époque, dans l'Allemagne de Weimar, un «Républicain de Raison» ("Vernunftrepublikaner"), ce qui le différencie évidemment d'un Oskar von Niedermayer. Son institut et sa revue connaissent un essor bien mérité au cours des années 20; ce sont des havres de savoir et d'intelligence, où coopèrent Russes et Allemands en toute fraternité. En 1933, avec l'avènement au pouvoir des nationaux socialistes, Hoetzsch cumule les malchances. Pour le nouveau pouvoir, les "Vernunftrepublikaner" sont des émanations du "marais centriste" ou, pire, des "traîtres de novembre" ("Novemberverräter") ou des "bolchevistes de salon" ("Salonbolschewisten"). L'institut de Hoetzsch est dissous. Hoetzsch est "invité" à prendre sa retraite anticipée. La fermeture de cet institut est une tragédie de premier ordre. Le destin de Hoetzsch est pire que celui de l'activiste politique et éditeur de revues nationales révolutionnaires, Ernst Niekisch. Car on peut évidemment, avec le recul, reprocher à Niekisch d'avoir été un passionné et un polémiste outrancier. Ce n'était évidemment pas le cas de Hoetzsch, qui est resté un scientifique sourcilleux.

Pour une approche grande-européenne de l'histoire

Dans la conférence qu'il prépare dès août 1945, et qu'il prononcera peu avant de mourir en 1946, dans sa chère ville de Berlin en ruines, Otto Hoetzsch nous a laissé un message qui reste parfaitement d'actualité. L'objectif de cette conférence-testament est de faire comprendre la nécessité impérieuse, après deux guerres mondiales désastreuses, de développer une vision de l'histoire, valable pour l'Europe entière, celle de l'Ouest, celle de l'Est et la Russie ("gesamteuropäische Geschichte"). Personnellement, nous estimons que les prémisses pratiques d'une telle vision grande européenne de l'histoire se situent déjà toutes en germe dans l'œuvre politique et militaire du Prince Eugène de Savoie, qui parvient à mobiliser et unir les puissances européennes devant le danger ottoman et à faire reculer la Sublime Porte sur tous les fronts, au point qu'elle perdra le contrôle de 400.000 km2 de terres européennes et russes. Le Prince Eugène a définitivement éloigné le danger turc de l'Europe centrale et a préparé la reconquête de la Crimée par Catherine la Grande. Plus jamais, après les coups portés par Eugène de Savoie, les Ottomans n'ont été victorieux en Europe et leurs alliés français n'ont plus été vraiment en mesure de grignoter le territoire impérial des Pays-Bas espagnols puis autrichiens; les Ottomans n'ont même plus été capables de servir de supplétifs à cette autre puissance anti-impériale et anti-européenne qu'était la France avant Louis XVI.

Le testament de Hoetzsch nous interpelle !

Mais le propos de Hoetzsch, dans sa dernière conférence, n'était pas d'évoquer la figure du Prince Eugène, mais de jeter les bases d'une méthodologie historique et sociologique pour l'avenir; elle devait reposer sur les acquis théoriques de Karl Lamprecht, de Gustav Schmoller (inspirateur du gaullisme dans les années 60 du 20ième siècle) et d'Otto Hintze. Il faut, disait Hoetzsch, développer une histoire intégrante et comparative pour les décennies à venir. En affirmant cela, il n'avait aucune chance de se voir exaucer en 1946, encore moins en 1948 quand, après le Coup de Prague, le Rideau de Fer s'abat sur l'Europe pour quatre décennies. En 1989, immédiatement après l'élimination du Mur de Berlin et l'ouverture des frontières austro-hongroises et inter-allemandes, l'Europe et la Russie auraient eu intérêt à remettre les propositions de Hoetzsch sur le tapis. Au niveau scientifique, des études remarquables ont été réalisées effectivement, mais rien ne semble transparaître dans la presse, faute de journalistes professionnels capables d'appliquer les leçons pédagogiques de Haushofer et de Radós. Les journalistes ne sont plus des hommes et des femmes en quête de sujets intéressants, innovateurs, mais bel et bien ceux que Serge Halimi nomme avec grande pertinence les "chiens de garde" du système. Les journaux et les revues constituaient la voie de pénétration vers le grand public dont disposaient jadis les instituts de sciences humaines et les universités; pour tout ce qui est véritablement innovateur, pour tout ce qui va à l'encontre des poncifs répétés ad nauseam, cette voie est désormais bien verrouillée, dans la mesure où les journalistes ne sont plus des hommes libres, animés par la volonté de consolider le Bien public, mais d'ignobles et méprisables mercenaires à la solde du système et des puissances dominantes. Toutefois, le défi que nous a lancé Brzezinski en 1996, en publiant son fameux livre, The Grand Chessboard, où sont étalées sans vergogne toutes les recettes thalassocratiques pour neutraliser l'Europe et la Russie, avec l'aide de cet instrument qu'est le complexe militaro-mafieux turc, —potentiellement étendu à toute la turcophonie d'Asie centrale— montre une nouvelle fois qu'une riposte européenne et russe doit nécessairement passer par une vision claire de l'histoire, vulgarisable pour les masses. Le destin tragique de Hoetzsch, son courage opiniâtre qui force l'admiration, sa modestie de grand savant, nous interpellent directement: notre amicale paneuropéenne a pour devoir de travailler, modestement, dans son créneau, à l'avènement de cette historiographie grande européenne que Hoetzsch a voulu. Au travail!

Robert STEUCKERS.

(Forest-Flotzenberg, Vlotho im Weserbergland, août 2002).

La noticia del apresurado y dichoso financiero yanqui, nos trae al recuerdo la figura del gran economista alemán profesor Werner Sombart, que ejerció docencia, justamente sonada, como profesor de Economía Política, en la Universidad de Berlín, y cuya obra es una verdadera pena que aun no haya sido traducida —que sepamos— al castellano.

La noticia del apresurado y dichoso financiero yanqui, nos trae al recuerdo la figura del gran economista alemán profesor Werner Sombart, que ejerció docencia, justamente sonada, como profesor de Economía Política, en la Universidad de Berlín, y cuya obra es una verdadera pena que aun no haya sido traducida —que sepamos— al castellano.

A recent study points to

A recent study points to  Documents which have circulated in connection with the Fay/Jones and Taguba Reports made clear that following the issuance of high-level legal advice outside normal Department of Defense channels, command authorities in Iraq no longer considered the Geneva Conventions to restrain them in their handling of detainees. Internal email traffic among military intelligence units is consistent: Once you label the insurgent detainees as “terrorists,” “they have no rights, Geneva or otherwise.” It seems highly improbable that officers carefully trained in the Geneva rules would suddenly discard them on their own initiative. To the contrary, it is reasonably clear that instructions to that effect were transmitted from a very high source. The Yoo memoranda are critical to understanding what happened, and the March 14, 2003 combined with the initial OLC advice concerning treatment of insurgents in Iraq are likely the most significant pieces of the puzzle not yet in place.

Documents which have circulated in connection with the Fay/Jones and Taguba Reports made clear that following the issuance of high-level legal advice outside normal Department of Defense channels, command authorities in Iraq no longer considered the Geneva Conventions to restrain them in their handling of detainees. Internal email traffic among military intelligence units is consistent: Once you label the insurgent detainees as “terrorists,” “they have no rights, Geneva or otherwise.” It seems highly improbable that officers carefully trained in the Geneva rules would suddenly discard them on their own initiative. To the contrary, it is reasonably clear that instructions to that effect were transmitted from a very high source. The Yoo memoranda are critical to understanding what happened, and the March 14, 2003 combined with the initial OLC advice concerning treatment of insurgents in Iraq are likely the most significant pieces of the puzzle not yet in place.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

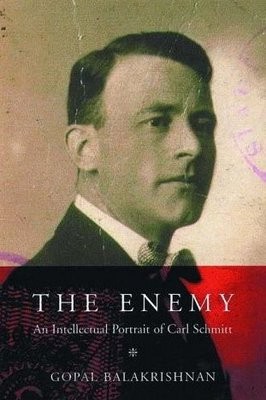

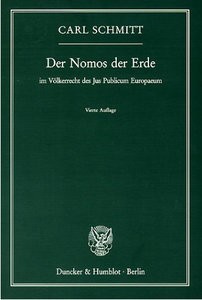

Digg Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre).

Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre). Arthur Moeller van den Bruck fu uno dei più alti risultati ideologici conseguiti dallo sforzo europeo di uscire dalle contraddizioni e dai disastri della modernità: fu uno dei primi a politicizzare il disagio della nostra civiltà di fronte all’affermazione mondiale del liberalismo e all’ascesa della nuova anti-Europa, come fin da subito fu giudicata l’America dai nostri migliori osservatori. Di qui una netta separazione del concetto di Occidente da quello di Europa. Il rifiuto dell’Occidente capitalista e della sua violenta deriva antipopolare doveva condurre in linea retta ad una rivoluzione dei popoli europei, ad un loro ringiovanimento, al loro rilancio come vere democrazie organiche di popolo. Come tanti altri ingegni dei primi decenni del

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck fu uno dei più alti risultati ideologici conseguiti dallo sforzo europeo di uscire dalle contraddizioni e dai disastri della modernità: fu uno dei primi a politicizzare il disagio della nostra civiltà di fronte all’affermazione mondiale del liberalismo e all’ascesa della nuova anti-Europa, come fin da subito fu giudicata l’America dai nostri migliori osservatori. Di qui una netta separazione del concetto di Occidente da quello di Europa. Il rifiuto dell’Occidente capitalista e della sua violenta deriva antipopolare doveva condurre in linea retta ad una rivoluzione dei popoli europei, ad un loro ringiovanimento, al loro rilancio come vere democrazie organiche di popolo. Come tanti altri ingegni dei primi decenni del

Man mag nicht glauben, daß 56 Jahre seit der Erstveröffentlichung des vorliegenden Bandes vergangen sind! Die Fragen, denen Sieburg sich hier in neun Kapiteln (etwa »Die Kunst, Deutscher zu sein«, »Vom Menschen zum Endverbraucher«) widmet, lesen sich nicht als Rückblick auf Gefechte von gestern. Sie sind noch ebensogut unsere Themen: Identitätssuche, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Konsumwahn, die Grenze zwischen Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit. Auch wo seine Angelegenheiten einmal der unmittelbaren Aktualität entbehren – etwa in seiner bemerkenswerten Replik auf Curzio Malaparte (d.i. K.E. Suckert) oder in seinen Einlassungen zum Verlust der Ostgebiete – nickt man staunend. Ohne Twitter oder Ryan Air gekannt zu haben, spottet Sieburg über »das Management des Vergnügens«, die »Mechanisierung der Freizeit«. Er meinte damit – wie bescheiden aus heutiger Warte! – »Betriebsausflüge an den Comer See« und Klassenfahrten in die Alpen. »Der Vorschlag, die Kinder sollten an der Nidda Blumen suchen, würde heute auf allen Seiten große Heiterkeit hervorrufen.« Für Sieburg waren die Deutschen »ein Volk ohne Mitte«: »Im Deutschen, so glaubte die Welt gestern noch, ist mehr Explosivstoff angehäuft als in jedem anderen Erdenbewohner. Hat sich diese Ansicht geändert, sind beim Anblick des fleißigen und lammfrommen Bundesdeutschen, der sogar den Karneval straff organisiert und wirtschaftsbewußt dem Konsum dienstbar macht, der das Wort Europa dauernd im Mund führt, (…) den kein Aufmarsch mit Fahnen mehr aus seinem Wochenendhaus, seinem Faltboot und Volkswagen herauslocken kann, der nur noch zu den Vertretern versunkener Fürstenhäuser und zu Filmstars aufschaut, der einen harmonischen Bund zwischen Preußentum und Nackenfett eingegangen ist, (…) der vom Golf von Neapel bis zum Nordkap die schnellsten Wagen fährt, sich in Capri bräunen läßt (…), der sich aus Ordnungssinn mit der abstrakten Kunst und dem Nihilismus beschäftigt – sind, so frage ich, beim Anblick dieses Musterknaben, der sich in der Schule der Demokratie zum Primus aufarbeitet, alle Ängste und mißtrauische Befürchtungen verschwunden? Ich antworte, nein.«

Man mag nicht glauben, daß 56 Jahre seit der Erstveröffentlichung des vorliegenden Bandes vergangen sind! Die Fragen, denen Sieburg sich hier in neun Kapiteln (etwa »Die Kunst, Deutscher zu sein«, »Vom Menschen zum Endverbraucher«) widmet, lesen sich nicht als Rückblick auf Gefechte von gestern. Sie sind noch ebensogut unsere Themen: Identitätssuche, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Konsumwahn, die Grenze zwischen Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit. Auch wo seine Angelegenheiten einmal der unmittelbaren Aktualität entbehren – etwa in seiner bemerkenswerten Replik auf Curzio Malaparte (d.i. K.E. Suckert) oder in seinen Einlassungen zum Verlust der Ostgebiete – nickt man staunend. Ohne Twitter oder Ryan Air gekannt zu haben, spottet Sieburg über »das Management des Vergnügens«, die »Mechanisierung der Freizeit«. Er meinte damit – wie bescheiden aus heutiger Warte! – »Betriebsausflüge an den Comer See« und Klassenfahrten in die Alpen. »Der Vorschlag, die Kinder sollten an der Nidda Blumen suchen, würde heute auf allen Seiten große Heiterkeit hervorrufen.« Für Sieburg waren die Deutschen »ein Volk ohne Mitte«: »Im Deutschen, so glaubte die Welt gestern noch, ist mehr Explosivstoff angehäuft als in jedem anderen Erdenbewohner. Hat sich diese Ansicht geändert, sind beim Anblick des fleißigen und lammfrommen Bundesdeutschen, der sogar den Karneval straff organisiert und wirtschaftsbewußt dem Konsum dienstbar macht, der das Wort Europa dauernd im Mund führt, (…) den kein Aufmarsch mit Fahnen mehr aus seinem Wochenendhaus, seinem Faltboot und Volkswagen herauslocken kann, der nur noch zu den Vertretern versunkener Fürstenhäuser und zu Filmstars aufschaut, der einen harmonischen Bund zwischen Preußentum und Nackenfett eingegangen ist, (…) der vom Golf von Neapel bis zum Nordkap die schnellsten Wagen fährt, sich in Capri bräunen läßt (…), der sich aus Ordnungssinn mit der abstrakten Kunst und dem Nihilismus beschäftigt – sind, so frage ich, beim Anblick dieses Musterknaben, der sich in der Schule der Demokratie zum Primus aufarbeitet, alle Ängste und mißtrauische Befürchtungen verschwunden? Ich antworte, nein.« Müdigkeit und Geschichtslosigkeit zeige, »die mit einer nie dagewesenen Nüchternheit« gepaart sei. »Nur der Deutsche schwärzt seinen Landsmann bei Fremden an, nur der Deutsche verständigt sich lieber mit einem Exoten als mit einem politischen Gegner eigenen Stammes (…), nur der Deutsche verleugnet Flagge, Hymne und Staatsform des Mutterlandes vor Dritten.« Als »dümmstes Schlagwort« seiner Zeit erschien dem Publizisten der schon damals opportune Vorwurf, »restaurative Tendenzen« zu befördern. Alles Große, Geniale, das Heldenhafte ohnehin, dessen die Deutschen einst fähig waren, werde nun verhöhnt und gegeißelt unter dem Vorwand, »daß die alten Zeiten nicht wiederkommen dürfen«. Ja, und wie furchtbar war auch der »deutsche Spießer!« Allerdings, so Sieburg, sei zu befürchten, daß der Spießer in neuem Gewand, nämlich mit »heraushängendem Hemd« nach US-Vorbild wiedergekehrt sei, und daß die »Vorurteilslosigkeit in der Kleidung, im Umgang mit dem anderen Geschlecht und den Nerven der Mitmenschen nicht eine höhere sittliche Freiheit und einen souveränen Geist« mit sich führe.

Müdigkeit und Geschichtslosigkeit zeige, »die mit einer nie dagewesenen Nüchternheit« gepaart sei. »Nur der Deutsche schwärzt seinen Landsmann bei Fremden an, nur der Deutsche verständigt sich lieber mit einem Exoten als mit einem politischen Gegner eigenen Stammes (…), nur der Deutsche verleugnet Flagge, Hymne und Staatsform des Mutterlandes vor Dritten.« Als »dümmstes Schlagwort« seiner Zeit erschien dem Publizisten der schon damals opportune Vorwurf, »restaurative Tendenzen« zu befördern. Alles Große, Geniale, das Heldenhafte ohnehin, dessen die Deutschen einst fähig waren, werde nun verhöhnt und gegeißelt unter dem Vorwand, »daß die alten Zeiten nicht wiederkommen dürfen«. Ja, und wie furchtbar war auch der »deutsche Spießer!« Allerdings, so Sieburg, sei zu befürchten, daß der Spießer in neuem Gewand, nämlich mit »heraushängendem Hemd« nach US-Vorbild wiedergekehrt sei, und daß die »Vorurteilslosigkeit in der Kleidung, im Umgang mit dem anderen Geschlecht und den Nerven der Mitmenschen nicht eine höhere sittliche Freiheit und einen souveränen Geist« mit sich führe.

Les revenus générés par cette activité éditoriale demeurèrent assez sporadiques, ce qui obligea les habitants de la Maison Fidus, auxquels s’était jointe la femme écrivain du mouvement de jeunesse, Gertrud Prellwitz, à adopter un mode de vie très spartiate. L’avènement du national-socialisme ne changea pas grand chose à leur situation. Fidus avait certes placé quelque espoir en Adolf Hitler parce que celui-ci était végétarien et abstinent, voulait que les Allemands se penchent à nouveau sur leurs racines éparses, mais cet espoir se mua en amère déception. La politique culturelle nationale-socialiste refusa de reconnaître la pertinence des visions des ermites de Woltersdorf et stigmatisa « les héros solaires éthérés » de Fidus comme une expression de l’ « art dégénéré ». Dans le catalogue de l’exposition sur l’ « art dégénéré » de 1937, on pouvait lire ces lignes : « Tout ce qui apparaît, d’une façon ou d’une autre, comme pathologique, est à éliminer. Une figure de valeur, pleine de santé, même si, racialement, elle n’est pas purement germanique, sert bien mieux notre but que les purs Germains à moitié affamés, hystériques et occultistes de Maître Fidus ou d’autres originaux folcistes ». L’artiste ne recevait plus beaucoup de commandes. Beaucoup de revues du mouvement « Lebensreform » ou du mouvement de jeunesse, pour lesquelles il avait travaillé, cessèrent de paraître. Sa deuxième femme, Elsbeth, fille de l’écrivain Moritz von Egidy, qu’il avait épousée en 1922, entretenait la famille en louant des chambres d’hôte (« site calme à proximité de la forêt, jardin ensoleillé avec fauteuils et bain d’air, Blüthner-Flügel disponibles »). L’ « original folciste » a dû attendre sa 75ème année, en 1943, pour obtenir le titre de professeur honoris causa et pour recevoir une pension chiche, accordée parce qu’on avait finalement eu pitié de lui.

Les revenus générés par cette activité éditoriale demeurèrent assez sporadiques, ce qui obligea les habitants de la Maison Fidus, auxquels s’était jointe la femme écrivain du mouvement de jeunesse, Gertrud Prellwitz, à adopter un mode de vie très spartiate. L’avènement du national-socialisme ne changea pas grand chose à leur situation. Fidus avait certes placé quelque espoir en Adolf Hitler parce que celui-ci était végétarien et abstinent, voulait que les Allemands se penchent à nouveau sur leurs racines éparses, mais cet espoir se mua en amère déception. La politique culturelle nationale-socialiste refusa de reconnaître la pertinence des visions des ermites de Woltersdorf et stigmatisa « les héros solaires éthérés » de Fidus comme une expression de l’ « art dégénéré ». Dans le catalogue de l’exposition sur l’ « art dégénéré » de 1937, on pouvait lire ces lignes : « Tout ce qui apparaît, d’une façon ou d’une autre, comme pathologique, est à éliminer. Une figure de valeur, pleine de santé, même si, racialement, elle n’est pas purement germanique, sert bien mieux notre but que les purs Germains à moitié affamés, hystériques et occultistes de Maître Fidus ou d’autres originaux folcistes ». L’artiste ne recevait plus beaucoup de commandes. Beaucoup de revues du mouvement « Lebensreform » ou du mouvement de jeunesse, pour lesquelles il avait travaillé, cessèrent de paraître. Sa deuxième femme, Elsbeth, fille de l’écrivain Moritz von Egidy, qu’il avait épousée en 1922, entretenait la famille en louant des chambres d’hôte (« site calme à proximité de la forêt, jardin ensoleillé avec fauteuils et bain d’air, Blüthner-Flügel disponibles »). L’ « original folciste » a dû attendre sa 75ème année, en 1943, pour obtenir le titre de professeur honoris causa et pour recevoir une pension chiche, accordée parce qu’on avait finalement eu pitié de lui.

Come sappiamo, dalla dissoluzione dell’ordinamento medioevale sorse lo Stato territoriale accentrato e delimitato. In questa nuova concezione della territorialità – caratterizzata dal principio di sovranità – l’idea di Stato superò sia il carattere non esclusivo dell’ordinamento spaziale medioevale, sia la parcellizzazione del principio di autorità (1).

Come sappiamo, dalla dissoluzione dell’ordinamento medioevale sorse lo Stato territoriale accentrato e delimitato. In questa nuova concezione della territorialità – caratterizzata dal principio di sovranità – l’idea di Stato superò sia il carattere non esclusivo dell’ordinamento spaziale medioevale, sia la parcellizzazione del principio di autorità (1).

Der 26. September 1996 war ein bedeutender Tag – auch wenn dies die Öffentlichkeit erst mehr als ein Jahr später erfahren sollte. An diesem Tag wurde Ernst Jünger in die katholische Kirche aufgenommen. Beim Gottesdienst zu diesem Anlaß wurde nach Jüngers Wunsch der Psalm 73 gebetet, in dem er die oft verschlungenen Pfade seines Lebens widergespiegelt sah:

Der 26. September 1996 war ein bedeutender Tag – auch wenn dies die Öffentlichkeit erst mehr als ein Jahr später erfahren sollte. An diesem Tag wurde Ernst Jünger in die katholische Kirche aufgenommen. Beim Gottesdienst zu diesem Anlaß wurde nach Jüngers Wunsch der Psalm 73 gebetet, in dem er die oft verschlungenen Pfade seines Lebens widergespiegelt sah:

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement

Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement

Bajo la fórmula “Revolución Conservadora” acuñada por Armin Mohler (Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschlan 1918-1932) se engloban una serie de corrientes de pensamiento contemporáneas del nacionalsocialismo, independientes del mismo, pero con evidentes conexiones filosóficas e ideológicas, cuyas figuras más destacadas son Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt y Moeller van den Bruck, entre otros. La “Nueva Derecha” europea ha invertido intelectualmente gran parte de sus esfuerzos en la recuperación del pensamiento de estos autores, junto a otros como Martin Heidegger, Arnold Gehlen y Konrad Lorenz (por citar algunos de ellos), a través de una curiosa fórmula retrospectiva: se vuelve a los orígenes teóricos, dando un salto en el tiempo para evitar el “interregno fascista”, y se comienza de nuevo intentando reconstruir los fundamentos ideológicos del conservadurismo revolucionario sin caer en la “tentación totalitaria” y eludiendo cualquier “desviacionismo nacionalsocialista”.

Bajo la fórmula “Revolución Conservadora” acuñada por Armin Mohler (Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschlan 1918-1932) se engloban una serie de corrientes de pensamiento contemporáneas del nacionalsocialismo, independientes del mismo, pero con evidentes conexiones filosóficas e ideológicas, cuyas figuras más destacadas son Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt y Moeller van den Bruck, entre otros. La “Nueva Derecha” europea ha invertido intelectualmente gran parte de sus esfuerzos en la recuperación del pensamiento de estos autores, junto a otros como Martin Heidegger, Arnold Gehlen y Konrad Lorenz (por citar algunos de ellos), a través de una curiosa fórmula retrospectiva: se vuelve a los orígenes teóricos, dando un salto en el tiempo para evitar el “interregno fascista”, y se comienza de nuevo intentando reconstruir los fundamentos ideológicos del conservadurismo revolucionario sin caer en la “tentación totalitaria” y eludiendo cualquier “desviacionismo nacionalsocialista”.

Keith Preston

Keith Preston is the chief editor of AttacktheSystem.com and holds graduate degrees in history and sociology. He was awarded the 2008 Chris R. Tame Memorial Prize by the United Kingdom's Libertarian Alliance for his essay, "Free Enterprise: The Antidote to Corporate Plutocracy."